In which the airline ferries millions of greenbacks every day to post-Soviet Russia for mail-order brides, orphans and the chance to see something carved from the Hope Diamond. (2010)

Before 9/11 flight attendants had more access to the flight deck. In fact, occasionally the pilots would allow us, against the rules, into the cockpit for takeoff and landing. It was from the cockpit, with my headset on and listening to the technical exchanges between the pilots and the tower that I first saw Russia, rising up from below us, the fall foliage stinging the air with color, the rooftops of dachas clustered below us as we made our approach in to Sheremetyevo International. Below us was America’s cold war nemesis now re-inventing itself after what seemed like the precipitous collapse of the Soviet Union, and all I could think of as the landing gear lowered and the gunmetal sky pressed down on us was that Reagan’s “Evil Empire” looked shockingly like anywhere else.

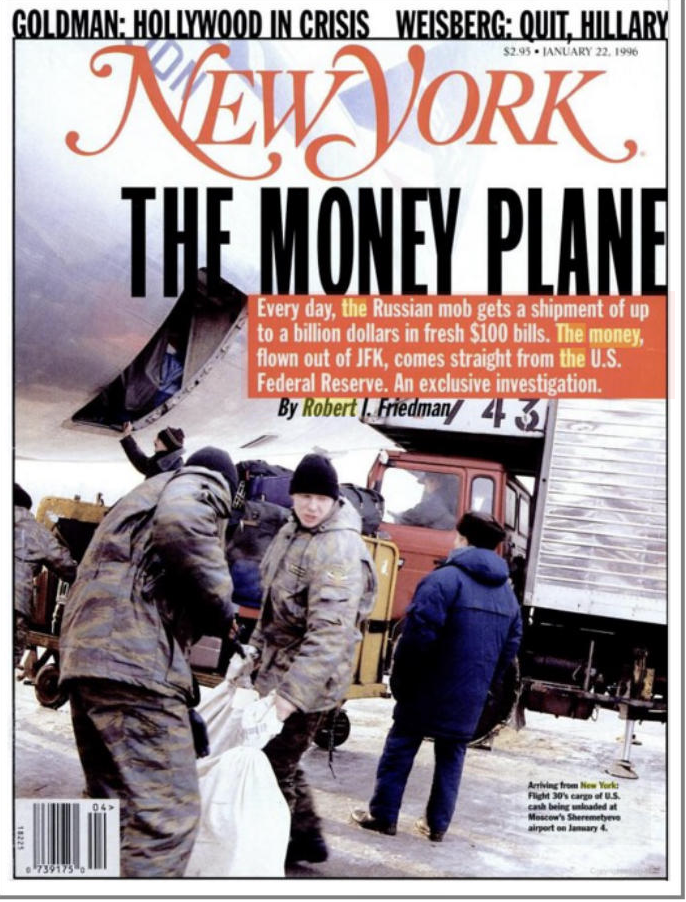

I didn’t know it at the time, but in the hold of first the MD-11 and later the Boeing 767ER which was the airline’s standard trans-oceanic equipment sat one million fresh hundred dollar bills, uncirculated, still in their Federal Reserve wrappers. In fact, every day of the week the only American airline with a non-stop from New York to Moscow, the carrier I worked for, loaded dozens of large white canvas bags weighing 2,300 pounds with an armored truck and guards at hand, into cargo: one hundred million dollars per day, sometimes more.

Between January 1994 and January 1996 federal authorities estimated that these C-notes totaling more than forty billion dollars had already made the trip, a total that far exceeded the value of all the Russian rubles then in circulation. Most of it, by then the unofficial currency of Russia, was going directly into the hands of the Russian Mafiya’s global drug trade, “as well as to buy the requisite villas in Monaco and Cannes,” according to a New York Magazine article that detailed the story.

Working flight thirty to Moscow and flight thirty-one back to New York, was an adventure in itself. Other than the expected depletion of the liquor kits in all three cabin classes, we carried not only the C-notes east, bundled and brokered by the federally chartered Republic National Bank, but Slavic brides west, sitting next to their new, Cabela-outfitted husbands in awkward silence for the ten-hour flight home.

In business class, former KGB spies sat dully next to the unarmed bank courier, the rest pilot, American tourists and Russian nationals. On one trip, a former Communist hack the size of a house, who looked Siberian and had one word for the crew during the entire flight (“cognac!”), took off both his shoes and socks and braced his feet on the back of the occupied seat in front of him. On descent, after readying all of his luggage and numerous bags of duty free, unsecured for landing, around his seat, he refused to re-stow all of it to the overhead upon my request. Crazy with fatigue from the long flight, I returned all of it, roughly, I might add, to the bins for him myself, while he sat grunting at me. While deplaning he asked where his folded clothes bag was at which point I gestured toward the lavatory into which I had slammed it just prior to landing. As the crew was loading into the hotel van the drooly-lipped mobster stood at the curb eyeing me and I feared for my life. We were in post-Soviet Moscow after all.

One early afternoon in 1997 we took off from Moscow loaded up with a sturdy box filled with the Romanov Jewels on their way to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington for an exhibit. They were stored in the aft cabin closet where we normally kept all the bags of everyone’s favorite airline munchie: peanuts. Ironically, the jewels which included pin with a blue diamond that may have been cut from the same stone as the Hope Diamond, as well as a ruby believed to have been owned by Julius Caesar was valued at $100 million–the same amount in dollars that we had brought over to Moscow from New York just over twenty-four hours earlier. During the cocktail service I made the mistake of reflexively opening said closet to collect a few bags of nuts, when not one, not two, but four Russian guards were at my side about ready to hit me over the head with what I figured would be their carry-on of a samovar. Later, at the gallery, so neurotic were the Russians about the trove that no one but Russians were allowed to touch the jewels as they were laid out in displays. The Corcoran show was only the beginning of the absurd Russian oversight of the jewels involved in a week-long standoff at the venue with Russian embassy vehicles blocking the van in which the jewels were to be transported.

Most notably, however—more so than the cash going one way and Russian jewels the other—were the orphans being shuttled back to the U.S. by Americans eager to adopt. We called Flight Thirty-one the baby bus. On one return trip I counted thirty-four crying, often traumatized children, mostly under the age of three. Unwittingly, airline employees had become part of the industry of placing Russian children in American homes which, we would learn later, didn’t always work out too well—for the children or their new parents. Clothing, shoes, and toys collected at American churches and community centers were daily packed by crews in huge suitcases, checked in cargo, and retrieved for distribution at Moscow orphanages. It was such a common practice that the transport became an agenda item during our pre-flight briefings with the pilots.

Earlier this year, a Tennessee mother “returned to sender” her seven-year-old adopted Russian son Artyem Saveliev after six months. Flying to Moscow as an unaccompanied minor, the boy carried a letter from Tory Hansen, reporting that she no longer wanted to parent the child who, she claimed, was violent and psychopathic. Fifteen Russian adoptees to date have actually been killed by their American parents, so I suppose I should be grateful that she only delivered the poor kid half away around the world on his own. On the baby bus, the new parents, usually both a husband and wife, settle in for the long flight back to New York, where most of them will take at least one other flight to points beyond. They have the same hyper-vigilance about doing the right thing that all new parents have, but perhaps even more so: many of them are older parents who might be checking something off their bucket list though, in their defense, all of them have been through some kind of bureaucratic hell getting these children to this point. As for the children, they are children, more restless than others perhaps due to the existential disruption, and, curiously, most with identifying marks on their shaved heads, stains of some kind that looks like a bruise, anti-lice powder, I am told.

I have a certain empathy for these parents, who are taking it upon themselves not just to be parents, but to give a safe and secure home to a troubled and often abandoned child. I know what it’s like to watch helplessly as a young person struggles to make their way in an unstable world, fraught with uncertainty. If it hadn’t been for Mark, Cath and I might have also been tempted to return Derek to sender. At least these folks had custody of their minors. At least they seemed to have financial resources for the adventure of child-rearing. And so we flight attendants became adjunct nurse maids for ten hours, relieving the parents of the incessant crying babies, the hurting ears on descent, the discomfort of all things new, the upset stomachs and voluminous vomiting upon landing at JFK.

Millions of Americans, like Cath and I, are raising their grandkids. In 2006 in was six million, and the number continues to skyrocket. More than a third of that population provides more than just food and shelter. They are considered “primary caregivers.” And half of that number are caring for their grandchildren for three or more years. Cath and I and presumably many others were and are without custody, without financial support—taking out second mortgages, cashing-out 401Ks to keep things aloft.

In truth, the whole experience of flying to Moscow and back was unsettling to me. It’s as if the trip were a relentless mirror being held up to us as to the excesses and contradictions of America itself. Its late-stage capitalist model. Its naïve narrative we’ve created about the fall of the Soviet Union as if we could just transplant our values, our way of life wholesale to the East. You don’t crater an entire superpower overnight without unrest, uncertainty for not only Russians but the world. And then there is this corruption fueled by the billions of American dollars that the airline is literally moving directly into Russian banks that have become the world’s leading money-launderers. At what point are Americans implicated in the role our country is playing in this organized crime, called Vorovski Mir or “Thieves’ World” that is the economic mainstay of Russia? Clearly the U.S. Treasury isn’t going to say anything, earning fifteen billion dollars a year from dollar sales abroad. It costs four cents to print a hundred-dollar note. The remainder of its face value goes back into its coffers until it is redeemed. In many cases, the difference between the four cents it costs to print the hundred-dollar note and the remainder of the face value on the bill is pocketed until the note is redeemed, which in many cases it never will be. “It’s an interest-free loan to the U.S.,” maintains Edgar Feiger, a University of Wisconsin professor and consultant to the Fed.

Outside of any concern for Russians and former Soviet states, outside of the concern for three thousand Russian babies being adopted, on average, every year, is the anguish over how America, supposedly the only superpower left after 1991, is compromising itself, implicated in the corruption of the “Wild East” by the American government’s looking the other way. Just how corrupt is it? Since 1992, crime was the only growth industry in Russia with illicit cartels controlling as much as forty percent of the nation’s wealth.

“Any time that dirty money can find its way into the U.S. financial system, it poses a risk to us,” says Jerry Rowe, the IRS’s chief officer of narcotics and money laundering, quoted in the New York magazine article. “It can, in fact, give criminals an opportunity to operate in a legitimate arena or buying up businesses.” The fear for Rowe and others stated as early as 1997, is that those companies could end up supporting political candidates, politicians who these companies think will be able to then cast a shadow for them in American society.

But that first time I saw Mother Russia outside the cockpit windows I sat with fascination at what could have been the countryside outside of Dulles International in Virginia. Earlier, before we had entered the sterile cockpit of landing operations, the Captain, a navy pilot-turned-commercial sky god earning close to a half a million dollars a year in salary, mused on what he saw as the enigma of Russia. “So much talent. So much accomplishment: engineering, technology, art.”

“Don’t forget philosophers,” chimed in the first officer. “And great writers.”

“But when it comes to government,” continued the captain through his mid-western drawl, “Jesus Christ. They just can’t get their shit together. What their leaders put their own people through. Americans will never understand what we have. That’s what the cold war was about. Freedom from tyranny.”

This chapter is from a book-length narrative fiction work set in the year 2010 (in search of a publisher) titled “Cold Desert: an Interstate Eighty Picaresque,” which placed 2nd in the Utah Original Writing Competition.