With Apologies to Tony Kushner

by David G. Pace

Below Ensign Peak sits Y. Rex Hyrum Callister Fielding Jorgensen, who by name alone is a blue blood. He sits atop a giant boulder, half a bag of chewed sunflower seed husks littered about him, binoculars to his eyes. He is focused on a house below him and the cherry red pick-up backing out of an arc-ed driveway, the white brick house framed by scrub oak, the back of the house stepping precariously down the hill into a second level. The pick-up waits for a passing car–the occupant of which honks and waves–then bumps out into the empty street facing nothing but the muddy mountain, the same mountain upon which Rex, thoughtfully cracking seeds, is perched. The pick-up slowly moves down the street, then down the hill to the city of symmetry ringed by violent, white-capped peaks. Rex holds his breath, a single seed wedged seam-side up between molars.

Six years ago, when he was eighteen, Rex broke into a gas station late one August night. As he sat in the office chair looking at the stapler on the desk and the wall calendar of scantily-clad women weighing down the hoods of cars, a certain euphoria came over him, a steady current of adrenalin that brought him enormous psychic relief. The same relief he hungers for now.

Rex watches as the front door of the house opens, and a young woman, holding a crying child on her hip, pads out in bare feet to pick up the newspaper. At the open door, another child, a twin, in nothing but a diaper, crawls into view, eyes wide. Through binoculars, Rex can actually see the dimples on the back of the crawling baby’s hands. Resolved, he bites down on the salted seed, his tongue expertly fishing for the meat. Tomorrow, on Sunday, this family will be in church at a ward house less than a five-minute walk away. They will not bother to lock their door in the safe neighborhood known as the Upper Avenues, and this residence framed in scrub oak will become the Sunday School Burglar’s third hit of the day.

Now it is April, 1983, and the shifting, water-logged mountains have opened their veins with a groan. Blood spills down their flanks in aspirating heaves, carrying trees and boulders, trucks and abandoned après-ski cabins. With their flinty tops these mountains are considered young, but they feel older than their years. The suspense of straddling a fault line threatening to slip has made them feel tired, worn, more Appalachian than Rocky. And now record snows, heavier-than-usual spring rains and finally, fierce, high-desert heat, crumple the glaciers into raging, exfoliating currents.

But something other than the dissolute mountain range’s need to purge is demanding a hearing. Something civic. It is the blood of the valley people that is crying out, blood that is blue, soul-less—not yet alive. Blood that needs to become red.

S. Einar Hinckley Packer Leavitt Allred, also a blueblood, carries a multi-segmented name that dates back to the time of the pioneers–of an English and Norwegian stripe–and today, he is sitting in the cab of his cherry red truck, waiting for the traffic light at North Temple and State in Salt Lake City. For days now, people have been sloshing through the intersection in the overflow from City Creek. Across the street rises the mighty Church Office Building, anchored as it is on a double-winged base, each side displaying an earth orb in bas relief–stone testicles to the tower above. The sight of this building always makes Paul feel inadequate, but he has not told anyone that, certainly not his blue blood wife, Donna Catherine Eliza Pratt Allred, home with the twins.

The light turns green, and Einar moves slowly into the intersection, the water hissing at his tires. Along the north side of the street, scores of tiny ministering angels are piling up. Eight inches tall and referred by acronym as “M.A.”s they have been fixtures in the city since the 60s when the Great Work of saving the dead was significantly stepped-up. Now they are everywhere in the city, unable to get their wingless, poochy-faced selves and their endless piles of names, extracted from old histories and records, across even three inches of water. Heavy laden, the M.A.s are headed past the Church Office Building and to the temple where the names will be added to the great lists of the dead who still need to be baptized by proxy.

Einar considers stopping for a moment to ferry the M.A.s across in the back of his truck, but there are too many, and he’s not particularly fond of them anyway. Too self-important. First one—his robe caught under the foot of another–starts to fret and then another lets out a cry as he inadvertently gets pushed off the crowded curb and into the gutter, gushing with water and leaves, sticks and small stones, water headed for the already flooded storm drains. Some of the extracted names float in the street like leaves: Thomas Germaine Miller, Susan DeBry, Benjamin Dubno. A speed bump in the Great Work, Einar thinks. That’s all this is. Nothing can stop the work of the M.A.s, immortal cherubim that they are. Paul decides they can take care of themselves. Besides, as a collective they only make him feel guilty.

From North Temple Street, Einar heads up Emigration Canyon to higher ground where he stops at Ruth’s Diner for coffee. The sun is blazing like July, three months early, and the plate glass of Ruth’s ricochets light. The sky is cloudless, and behind the diner he can hear the roar of what is normally a babbling creek. This year the creek, frenzied as a high school cheerleader, is swollen, rushing down the canyon on its way to enter the exit-less Great Salt Lake.

Inside the Diner, Bishop D. David Mitchell sits at the counter, reading The Salt Lake Tribune. Upon seeing the back of the bishop’s head with its signature bald spot the shape of the African continent, Einar does a military one-eighty and heads back out. Can’t be ordering contraband coffee in front of his bishop, he is thinking. But Bishop Mitchell sees Einar before he can leave.

“What a pleasant surprise, Brother Allred,” says the bishop with a limp grin. “Didn’t think I would have the pleasure of interviewing you over breakfast.” There is no such thing as a conversation with one’s bishop. Only an interview, even (especially) when it is masked as a conversation. Einar considers that at least Bishop Mitchell doesn’t pretend otherwise. The bishop pats the stool next to him. “Quite the spring we’re having.” Einar edges to the counter and returns the bishop’s handshake, hearty and invasive.

“Wreaking havoc downtown,” says Einar as he sits. “I’ll have a Sprite.” This to the waitress who has materialized with a coffee pot. She smiles, retreating with the pot and leaving the fragrance that Einar always holds in his head like a warm chestnut. It is the rich, distinctive smell he first experienced when he spent a childhood summer helping out on his uncle’s ranch in Idaho.

“We’re gonna need sandbag crews,” says the bishop. He jabs at the front page of the newspaper. “No one’s ever seen anything like this. Entire town of Thistle under fifty feet of water. Railroad can’t get through Spanish Fork Canyon down to the coal mines in Price. Makes you wonder if the second coming of the Lord isn’t upon us.”

“There’s M.A.s floating down the gutters on North Temple,” says Einar. “I guess that’s gotta mean something.”

“No kidding?” says the bishop. “Wonder if the prophet knows about it.”

“I would’ve stopped to help ‘em out,” says Einar referring to the ministering angels. “You know, get some of ‘em at least cross the street–but the traffic was ridin’ my . . . pushin’ me from behind.” Einar looks over the bishop’s shoulder when he says this, hoping his half-lie will float past the bishop and into the corner of the diner where a broom stands.

“Haven’t talked with you for a while, Brother Allred. How’s your father and the pipeline business?” Einar understands they are talking in code. To talk to the bishop means to confess something. Einar considers what he might confess to his bishop over Sprite and the newspaper at Ruth’s Diner. Aside from drinking the dreaded bean beverage, and the stray erection he lingers over in the shower, there is the little item of the temple where not only the Great Work for the dead is performed but marriages for the living—as in his sister-in-law’s coming up next week. Yesterday, he told Donna he will not be going to the wedding.

“Why not?” she said, a spoon of yellow puree suspended in front of their son’s drooly-lipped mouth above the tray of the high chair. The boy looked at him and smiled, his mouth full of the stuff, and Einar felt a stab of affection for the little guy, a reminder that no matter what catastrophe might befall him and Donna and the whole world for that matter, it was enough that he had had this one moment to love this sticky child. Even so, as he looked over his shoulder to check on the boy’s twin sister, he steeled himself before answering his wife’s question.

“Recommend’s expired,” he said. How could he tell her that he had no plans to renew it? He turned abruptly toward the kitchen where he waited for the squall to come from behind, the sudden cloudburst that was Donna’s trademark. When they were dating he admired her outspoken nature, so different from the other young women’s. Yet, ever since the twins were born, she and the sisterhood at the women’s auxiliary seemed to have crocheted their faith into a noose that Donna brandished whenever she sensed Einar wasn’t living up to the standard. Which lately seemed to be often.

“S. Einar Hinckley Packer Leavitt Allred,” she said, and he knew he was in deep trouble. She poked him in the chest with the half-filled spoon. “Bishop Mitchell is on to you, and it’s making us all look bad. Would you like me to make an appointment for an interview, or will you be doing it? I’m waiting.” The puree dripped down his fresh T-shirt.

That was the squall yesterday, which actually aroused Einar, as these squalls are wont to do. But what Donna does not know is that Einar’s “recommend,” the result of an annual worthiness interview with the bishop, has not simply expired. It cannot be renewed. To make ends meet for the past six months, Einar has been secretly spending their tithing, the requisite contribution necessary to pass through the temple’s Checkpoint Charlie and gain access to the wedding of Donna’s sister.

Einar looks at Bishop Mitchell. This meeting could not be a coincidence. He has never seen the bishop at Ruth’s Diner, known not only for its insufferably crabby owner, but for its coffee-drinking “gentile” clientele. That was why Einar went so far up Emigration Canyon in the morning for his coffee. The only Mormons at Ruth’s were like his aunt and uncle in Idaho, coffee and liquor-imbibing Jack Mormons who cannot get into the temple anymore for family weddings. The kind of Mormon Einar is fast becoming.

“I have a confession to make, bishop,” says Einar.

Back in the city, the Sunday School Burglar parks along the gentle grade of 2nd East Street and turns off the engine. He pulls his baseball cap down to better shade his eyes. The gutters are brimming with a soup, rushing with purpose yet somehow silent in the concrete troughs. Outside the car, the air is preternaturally heavy. A flock of birds skitters out of a tree, dips sharply toward the ground then makes formation and bolts west. Nothing else seems to be in motion, as if the earth were holding its breath, waiting.

For two years, while serving what has, since the uptight M.A.s’ arrival, become a required church proselytizing “mission,” Rex was known simply as “Elder Jorgensen.” And even though he resented being shipped off at age nineteen to Denmark for two years to preach the Mormon gospel in his family’s ancestral home, he actually came to like his new moniker. Not because it was an ecclesiastical title, but because he was no longer called “Rex.” But now, back at home, he is faced again with the one

thing he hates most about himself. His name. The first initial, “Y,” doesn’t stand for anything, which sometimes gets him into trouble when he is filling out tax forms. And he can’t just call himself “Y.” (“The name’s Y.” “Why?” “Yes.” “Excuse me?” “I don’t know why.” “What?” “No…Y.”) Much too confusing.

So he goes by “Rex,” one of those antique names stemming from the days of polygamy when families had, literally, scores of children and unused names were scarce. To him, “Rex” is unbearable, the name of a backroom school janitor who always smells funny, or a drifter waiting in line at the shelter near the Greyhound station. Not to mention the petulant TV-ad cat with the same name. Rex takes some solace from the new name with which he was first endowed in the temple as a departing missionary–a name he can be proud of. “John,” meaning “Yahweh is gracious.” And more importantly to Rex, the name recalls John McEnroe, the fiery, bad-ass tennis player who destroys his racket after losing a game and verbally abuses the chair umpires. The problem is, the new name is not for this life, but for the next and, per protocol, it can never be spoken to anyone–not even to one’s own future wife. More evidence that the universe has it out for him.

It was nine months ago when Rex was struck by a plan. It happened while he stood during sacrament meeting so the congregation could “sustain” him as the new assistant scoutmaster, and it was then, with old Sister Vogel’s face beaming up at him like a searchlight, that it occurred to him that everyone who lived within four square blocks was at that moment sitting in the chapel, every house within the ward boundary vibrating only to the sound of a roof-installed evaporative cooler. Empty. Waiting to be burgled. “All in favor of sustaining Brother Rex,” he remembers his own bishop intoning at the podium, “indicate so by raising the right hand.” My sorry, mismatched name justifies any career choice, thought Rex as he sat in church. Why wait for the next life to be justified and recompensed? In short, Rex the blue blood had a revelation, as blue bloods are wont to have. It was unorthodox, but what true revelation isn’t? Maybe he was a believer after all.

Of course Rex wasn’t going to case his own neighborhood. He would plant himself in the foothills of the wealthier snob hill domiciles and wait. That was twelve casings, followed by eleven hits ago. The Sunday School Burglar has even made the papers.

On the sidewalk, coming toward Rex, are two dogs, collared, but free-ranging, a black lab and what looks like a cross between a shepherd and a malamute. They zig-zag on the sidewalk, as if on a string operated from above. They sniff at the rushing water, whimper and turn, circling back around where they were earlier, then starting in a new direction. It occurs to Rex that these dogs do not know each other, and that any moment on one another, not out of some kind of alpha-dog angling, but out of inexplicable fright. In the gutter Rex notices a stray name that must have been caught by the wind or a passing car barreling up the hill and deposited here in a temporary eddy before it breaks out and continues its journey back downhill. The name is Rex Jarlsberg, the recently deceased bantam weight boxer whose real name was Reginald. Not like Rex, who is just a “Rex.”

Tomorrow, the Sunday School Burglar promises himself, he will take a few weeks off from his new career, maybe get out of town, lay low. “Place is starting to give me the creeps,” he mutters to himself.

Back at Ruth’s Diner: “I have a confession to make, bishop,” says Einar. Bishop Mitchell carefully folds the newspaper and lays it on the counter. A mantle of ecclesiastical solemnity descends on him. He laces his fingers together on the counter and leans in. But before Einar can say anything the diner begins to shake, and the roar of the creek out back crackles and booms. It sounds as if a train were barreling toward the tiny canyon diner. The broom dances out of the corner in three small bristled hops before falling to the floor with a smack, and old Ruth herself makes a rare appearance in her flowered house dress, a forgotten cigarette clinging to her trembling lips.

The bishop’s face goes white.

By the time Einar and the bishop get to Einar’s truck, the narrow road is filled with mud six inches thick, and the smell of clay and rock and uprooted trees is everywhere. Ruth, clinging to her broom, has refused to evacuate with them, so it is just Einar, Bishop Mitchell and the waitress, whose white uniform pants are now muddy up to her crotch so that it looks as if she is wearing hot pants. Down the canyon fly the three of them, dodging the biggest of the rocks and sliding haphazardly over sludge that shoots over the front of the hood and onto the windshield while underneath it cakes up in the wheel wells and grinds noisily.

“Better get to that sandbagging,” says Einar to the bishop. In between them sits the waitress, trying to avoid straddling the stick shift with her red legs.

“Will Ruth be alright?” she asks, a hand flat against the ceiling of the truck cab as they fling themselves down the canyon like a giant bat at dusk.

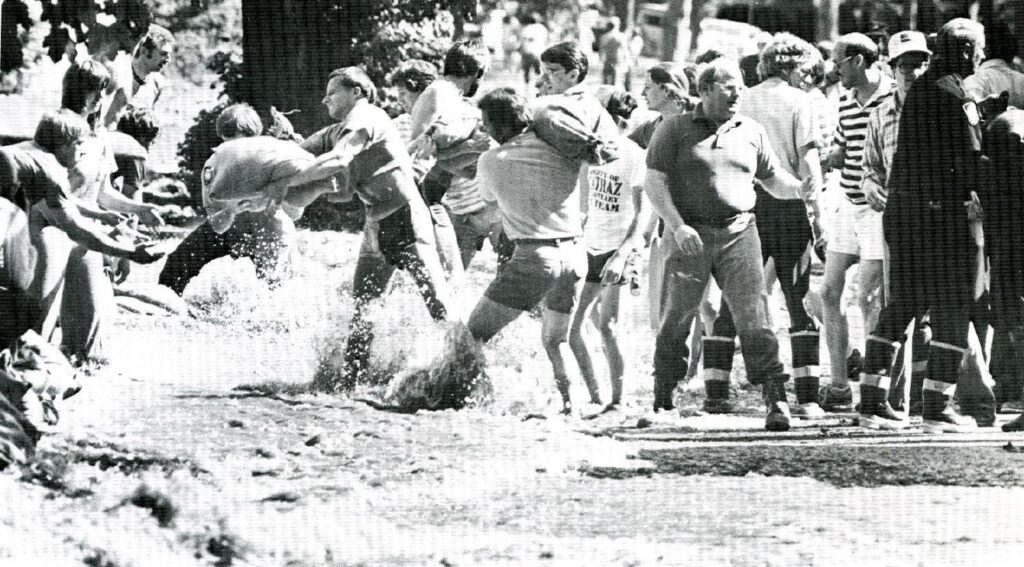

The following day is the Sabbath, and mid-way through priesthood meeting word is received from the pulpit in every ward along the Wasatch Front that, Sunday or not, the ox is in the mire–up to its prepuce in runoff. All able-bodied persons are needed immediately for sandbagging. Over at the cathedral, Father Sanchez gets a whispered message at the altar from an acolyte, flaps through the 10 a.m. mass double-time and shoos everyone out onto the street. All seven of the valley’s major drainages are well above flood levels. The city at the bottom of the hemorrhaging mountains is under siege, every one of its arteries swollen and purging. The canyons are rumbling, crying in the wilderness. And in the city, sandbagged rivers quickly begin to take form, directing red water down State Street, Thirteenth East and Ninth East Streets toward the Jordan River and an expanding Great Salt Lake.

The Great Work of name extraction and saving the dead slip-slides to an oozing halt. The temple doors closed, its workers sent home. M.A.s are swept away by the thousands along with the names they have mined from the public record. Some of the tiny workers are rumored to be hiding out on the second floor of the Hotel Utah where there is angry talk of organizing. And ensconced in the quiet, upper rooms of the temple itself, the white-haired prophet peers out of one of the distinctive, oval-shaped windows faceted into the thick granite walls. A modern-day Noah in his ark. For a long time he watches his charges, still in their Sunday best, high-stepping through ankle-deep water and carting sandbags. Occasionally, one of the workers bends over and hooks the tail of a “g” or the crossbar of a “t” of one of the many names being swept away.

Above, the sky is as dark blue as the blood of the freshly resurrected dead. Blue as the blood of God the Father and his Son Jesus. And all this red water, pouring out of the hills like the blood of a true mortal . . . well, it is disconcerting to the weary prophet who is the mortal closest to becoming a full-blown blue blood even before he dies and goes to the celestial kingdom. “I’m not sure I can handle any of this,” he says, and the heavy drapes on the oval window fall back as he shuffles away in his white slippers.

Even Father Sanchez, a Catholic, is aware of the local belief that what makes one immortal is that one’s blood becomes slowly replaced with a spiritual fluid, matter so fine as to elude the scientific lens. It is a fluid void of the corrosive effects of blood. It is “blood” that has been blued by faith and obedience and is therefore no longer the carrier of death. What’s known as blue blood is the very font of one’s exaltation–not like the M.A.s, the ministering class–but exaltation as the gods are exalted. It is the blue bloods—the improbably righteous–who will eventually stake their claim in the heavens as new gods, as the creators of new worlds and of new souls.

In this valley, one aspires to blue blood, to resurrection as a deity and to be with one’s exalted loved ones for eternity. This is the reason for name extraction. Saving ordinances must be performed in the temple for every person who has ever lived and died. So that all of humankind can merit their way into blue blood for the eternities. When Father Sanchez first arrived as bishop of the diocese, he wrote a stinging newspaper editorial about the practice of “saving the dead” by proxy baptism. But now? He grudgingly accepts it. One year after his death, per stipulation, his own name will show up in the temple, and he will be baptized vicariously, and by the true priesthood, so that in the hereafter his blood will be “blued.”

In the meantime, he maintains his Roman faith as much as he can among all these peculiar people.

Despite this understanding of a blood substitute spawned by obedience to a higher law, Einar–father of twins and husband to a full-of-faith and anxious wife–does not stop his foraging for morning coffee, an intractable entitlement that colors Einar’s blood pink if not red. On this Sunday morning, when he gets a call from the ward house that they need his truck up Little Cottonwood Canyon to carry sand baggers, he uses it as the day’s excuse to get his morning fix. To stave off criticism or invasive questioning by his fellow ward members, he puts on his Sunday uniform–white shirt and tie–before heading out to throw bags on the Lord’s Day. On the way out, he meets a teary-eyed Donna at the door.

“What is it, muffin breath?” he says, and she bursts into tears. The perpetual platelets of anxiety that course through her veins bubble up to her eyes and flood forth at his question–casual (and fearful) as it is.

“I . . . (sob) . . . want . . . (inhale) . . . to be . . .” she begins waving her hand in front of her contorted face, struggling to collect herself. “I want you at my sister’s wedding, Einar. Everyone will notice that you’re not there. They’ll wonder why, and they’ll wonder the worst.” Einar wishes he had taken that load of M.A.s to dry ground the day before. His report back to Donna of the deed would have stanched this moment, he thinks, standing with his hand on the knob to the front door. But now, she is sobbing in front of him so loudly that the twins begin crying as well. Jenny sits down hard on her diaper, her lower lip curling in under fat cheeks, and her brother Jason begins a wind-up like his toy choo-choo train before letting out a piercing whistle shriek.

Einar reaches for Donna, wrapping his arms around her and patting at her moist back. “Now, now…” he says, galvanizing into the family patriarch. “Look at you, all of you. What is all this? We already have enough water works out there without . . ..” He kisses Donna on the forehead and cheeks, and then she reaches for Jason. Einar instinctively starts for Jenny. They stand, jostling the twins.

Isn’t that enough? he thinks to himself later after leaving home and driving along Wasatch Boulevard to the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon. It isn’t the promises of the hereafter that make him want to love his wife. It is her body, the sweet sag of her postpartum can, the fragrant notch in her neck. Her smell. The twins are just a happy, natural consequence of that. It isn’t because of her righteousness that he wants her–although Einar is the first to acknowledge that Donna’s demonstrated rectitude initially helped close the deal with his family. No. It is the way Donna’s breasts move under that limp blouse when she bounces up and down during volleyball. The pounding of blood in his head and in his loins. It is that, and it is more. It is the tang of dirt and pine in the morning before he fires up his backhoe for a day’s work on the canyon roads. The distant sparkle of the lake as he drives, sweaty and weary, back home for dinner. It is the way the sun bakes his back when he is washing the truck. The comforting click of Donna’s Sunday heels on the kitchen floor as they head out to church. The way his daughter sleeps on her stomach, her knees up under her belly like a Muslim at prayer. Isn’t all that why they were here?

Why all this posturing toward eternity? The cool, antiseptic embalming of immortality? The Great Work of temple ordinances, genealogy–saving the dead? What doth it all profit? The most excitement he has ever had on any Sunday is today, with people’s homes roiling in danger, the regularity of church meetings torn to shreds as everyone drops their scriptures for a shovel.

Meanwhile Rex is delirious. Not only has everyone in the neighborhood gone to church but evacuated wholesale in a sort of reverse rapture down to the valley where they are now filling sandbags, assembling baffle boards and lustily singing,

Put your shoulder to the wheel, push a-long.

Do your duty with a heart full of song.

We all have work, let no one shirk,

Put your shoulder to the wheel . . . .

They pass sand bags hand-to-hand, exhilarated by the warm silt in their shoes, the splash of the mountain blood in their faces. The young mothers, taking snapshots and fixing sandwiches, move with their children to higher and higher ground. Even the prophet, having swapped out his slippers for boots, has gone against the counsel of his more circumspect apostles, and shown up with a smile and a wave at the exhilarated crowd.

The streets above the city are so empty that Rex thinks he must be cheating the universe. He whistles as he closes his car trunk on the spoils of the first two hits. Every resentment harbored deep in his sternum seems now to be uncoiling like a spring. When he gets to the third and final house, he walks up the arc-ed driveway and straight through the front door triumphantly singing, “The morning breaks, the shadows flee . . .”

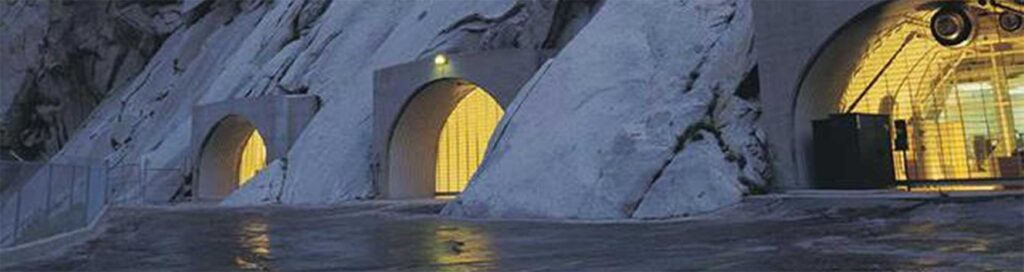

At the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon, Einar loads his truck with two other men and sandbags. Then they head up. Their destination is the Granite Mountain Records Vault, embedded deep in the north wall of the canyon. The very headwaters of the Great Work.

Today the protective vaults are threatened by the rock in which they rest, once thought to be immovable by quake or flood. Einar has been here as a teenager when his class toured the stacks of microfiche to which librarians were transferring the records. Brother Schmidt, a bald man with a pointed nose, was dwarfed by the shelves, and when he spoke of how much of the vast project of collecting the names of all earthly inhabitants had actually been completed, he compared it to five inches of the one hundred-yard football field at the U’s Rice Stadium. The students, including Einar, all gasped at the enormity of the task that lay ahead for the salvation of humanity, and Brother Schmidt smiled.

But now the massive name extraction program is imperiled. When Einar and the sandbaggers make the hairpin turn into the parking lot of the giant vaults, they are horrified to see water and mud spurting out from under the six heavy Mosler doors, and old Brother Schmidt, trembling and crying, his hands placed forcefully on the surface of the middle door, up to his ankles in rushing water and mud.

“Gå opp!” shouts Einar in what little Norwegian he’s picked up from his maternal grandmother. “Pony up, brethren!” And he shifts into four-wheel drive. “Levee the bags, beginning over there, berms over there.” He points to crumbling rock on the east wall. The plan is to keep the flow moving out and away from the doors, through the parking lot and down the canyon, so that the doors can be safely opened and the back-up in the catacomb of names minimized.

Above the working men is another vault–the cloudless sky which lies impenetrable to the drama of shoring up the mountain, and suddenly Einar senses the futility of it all. He has lived the measured life some twenty odd years–living by covenant, by program, by sheer dint of self-control. But all of it, as in this mountain cracking as it is now below the towering peaks, suddenly seems both inevitable and awesome. It is a world that eludes a prophet’s prophecy, a world that is necessary and catastrophic and limns Einar’s brain, his heart and his balls all at the same time. Something he has glimpsed in determined movements of his children as they push back against the world while simultaneously surrendering to it, a kind of tango that innervates the creation rather than depletes, cools and sterilizes creation, arouses it.

It is color as opposed to structure. It is how blood returns indelibly to the color red.

Once inside the third house, Rex feels empty instead of energized. This is different. He tries to organize his thoughts, make a plan, a sweep through the house that has the lived-in baby smell of twin toddlers, something stale, something sour. He looks at the pictures on the wall, of a man and a woman in wedding attire, the tuxedo-ed man stiff and broad as a nutcracker, she, in practiced repose–lace everywhere. He no longer believes in the eternities, or marriage, and now in his element he should feel the relief of acting as he truly is, at shedding his usual performance of the righteous, recently-returned missionary, the assistant scoutmaster looking for a wife. But he feels more unease than relief.

He sits back on the couch and remembers the last time he has been this smart. Or at least thought so at the time. It was when he was in Copenhagen. He was training a new missionary companion, one Elder Stewart, nineteen-years-old and fresh off the plane from Utah. The two of them have just been told by their number one prospective convert that she has decided not to go through with her baptism the next day.

“Can I ask you a question?” says Elder Stewart that night as they readied for bed, their gloom punctuated by a persistent Danish drizzle. “Do you sometimes question what we’re doing out here? That it’s really all that we say it is?” It is a moment for Rex that seems trite in the face of his own doubts that have long turned secretly cankerous, and he takes enormous pleasure in telling the young man, “You don’t really think any of us actually believe any of this, do you?” And then, with all the malice he can muster, “Oh . . . sorry . . . do you?” The next day Rex awakens to an empty apartment. Elder Stewart has left. Gone home.

Tyrannosaurus Rex. Just living up to a name he never chose.

When the mudslide starts to splinter the front door, Rex first thinks it is a pack of mad dogs. For a moment, he actually considers looking through the door’s peephole, but then he finds himself instinctively backing up toward the stairs that lead to the first floor and, hopefully, a way out. But downstairs he finds a river of the red silt that is becoming thicker by the moment, piling up against the sliding glass door like gravel in the bottom of an aquarium. The door leads to the back yard and down the steep slope of the mountain. He hears the sound of something knocking–three hard mallet knocks–and turns to watch the mud pour out of the heating vents in the living room where he stands, shell-shocked.

Rex is encased in mud, dead, and thus finally answering to the name, “John,” his secret new name given to him in the temple. Outside, the chimney spouts mud. Red, coarse and hot.

The western-most vault gives way first, the men barely able to snag Brother Schmidt and scramble up a rise to safety. The great door, rounded at the top, begins to sigh and pop. Bolts with heads the size of silver dollars wriggle loose and then, consecutively, from the bottom of the door up, shoot out of their respective bays like missiles. Granite rock splits all around the door which after the slightest, quietest of moments crumples like tin, and there is a rush of water, red mud and stone. The men scramble further up the rise, barely able to shout at each other over the chaos of the mountain giving way. Then a second vault collapses, and out of the cracking granite caves come the names, first two of them stumbling up and out of the rubble, newborn foals of Anson F. Livingstone and Abu Jabbar–followed by a rush of others–Susan Channing Jones, Markus Randall Klink, Solange LaCoeur, John Jasper Jenkins, and then a whole stampede of Mohammed Alis. All of them materialize from the microfiche and film records of marriage indices, parish lists, census reports, pilgrim registers, necrologies, all of the names pouring out, bumping up against the embankments, swirling around a single sandbag still poking its ears above the deluge. The names move out and around the corner of the parking lot, where two of them–Artaxiad and Ibrahim–simultaneously rise out of the water like jumping fish, shiny in the afternoon light, then down, down toward the mouth of the canyon.

The shifting, water-logged mountains continue to open their veins with a groan. Mountain blood mixes with the fecund undergrowth of juniper pine that clings to granite flanks by mere tendrils, it turns over and flees downhill, west toward the valleys and the lake. Under the blinding, high-desert sun, the threat to home and body is also the carrier of life. It sops the desert floor, it pushes back against the temple doors, it laps tantalizingly around the giant tower of the corporate church. It seeps through, bowls-over and undermines the holy city with its natural, alkaline charms. And out of Little Cottonwood Canyon the wild, earthen blood carries millions of names–Lawrence McAllister, J.B. Hunan, Chaim Lieberman, Cynthia Moy, Marilyn Virzi, David Kerekang, someone Said. The names spin blithely downstream, bruised but happy. Stories will surface later about a Ninth South Street eddy where a family of Tiengs from Cambodia was caught with a family of Lees from Korea, and about how a Jacob Fleischer was hooked into the “O” of an Omar Nader. Red Butte river and City Creek tangling with Parley’s and the Cottonwood Canyons drainages. The pond in Liberty Park will become known as Alphabet Soup.

From the mountains where Einar has climbed above the vault to wait out the flood, he looks out over the valley and watches the silver names tripping over boulders and around buildings–and of course each other as they head out to the Jordan River and the mighty, bloated great and salted lake. There they lie flat against the still surface of the brackish water, the late-in-the-day sun reflecting off them like light off the iridescent scales of cutthroat trout. Einar’s skin is ruddy with the pulse of life flowing beneath it, the veins in his arms blue through skin, but red as mountain mud. With their work in ruins, thinks Einar, maybe the M.A.s will pack up and head out. Standing there and looking over the valley, the curious sense of relief he’s felt since the vault has given way now turns to compassion for them, for the M.A.s, burdened with names, and he wonders if maybe he should suggest to the bishop, when they all get back to the ward, that they start some kind of retraining program for M.A.s. A Perpetual Emigration Fund for Ministering Angels.

Then overhead Einar hears a sound, like a bird. When he looks up he sees Ruth from the diner, last seen hunched over her broom. Now she is balanced on that broom, gliding on a warm updraft while she tries to light a cigarette. He thinks about his Donna and the twins, safe at his in-laws on the valley’s west side. Then S. Einar Hinckley Packer Leavitt Allred finds himself craving a cup of aromatic coffee, black.

This story is part of a collection of stories due out later this year (2023) titled “American Trinity and Other Stories from the Mormon Corridor” by BCC Press. It was originally written in 2005.

Copyright, David G. Pace 2023